Design innovation then/now: Designing infrastructure

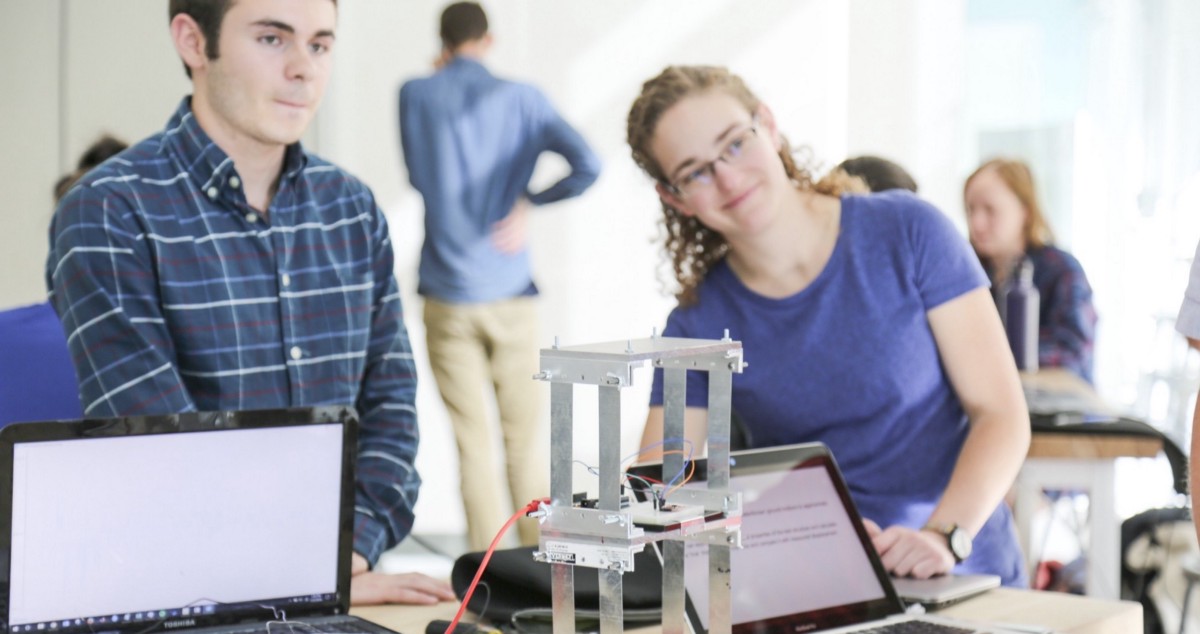

Design of Cyber-Physical Systems students with a prototype for evaluating post-earthquake structural damage. In celebration of UC Berkeley’s 150th birthday, we’re exploring Berkeley-driven design innovation from 1868 to today. Over the course of the year, we’ll take a look at researchers, creators, and makers who have been part of Berkeley’s Read more…