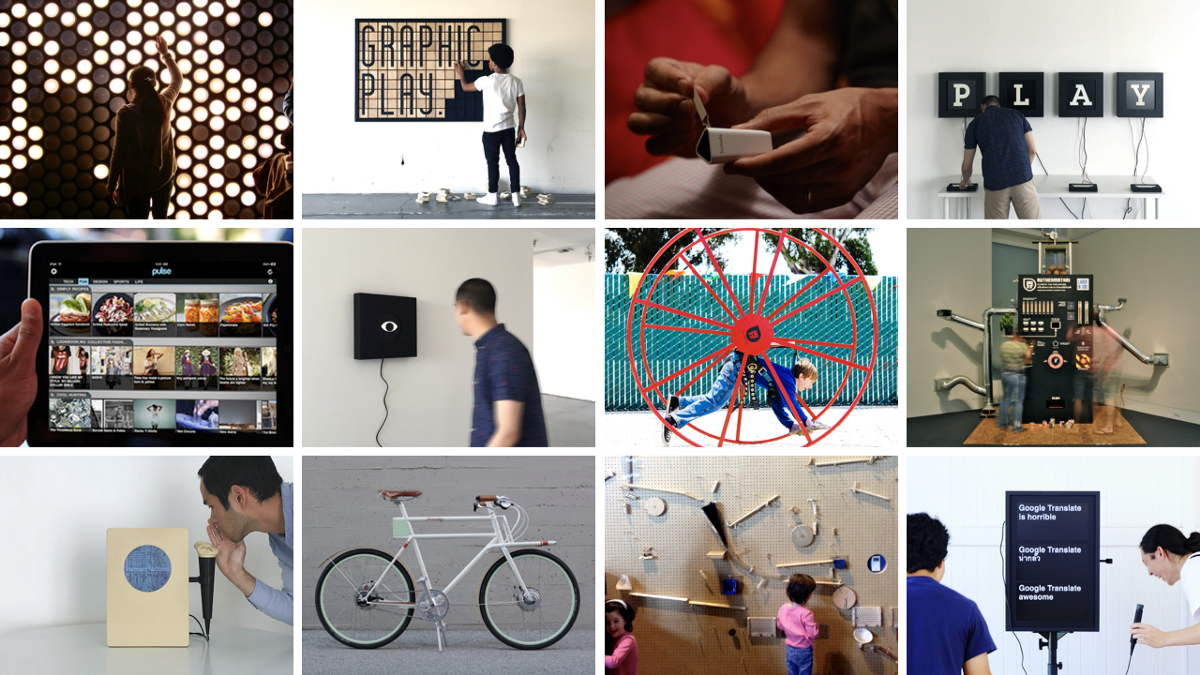

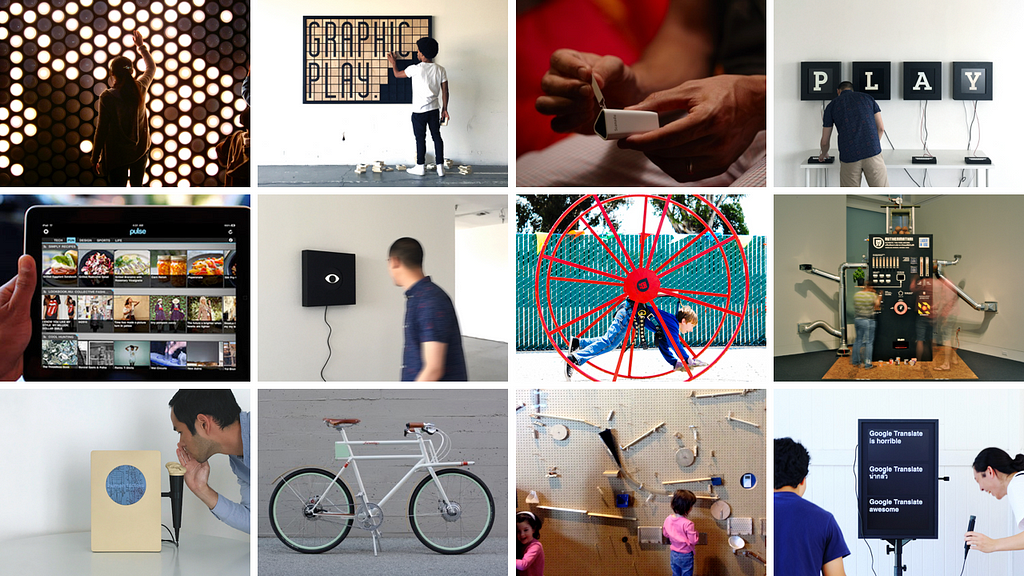

This fall, we welcomed a diverse group of speakers to Jacobs Hall for the Jacobs Design Conversations and Design Field Notes speaker series. With speakers ranging from artists to product managers, these talks’ topics covered a broad swath of the design field. Across these wide-ranging discussions, here are some common themes we heard.

Today’s designers should strive to understand the interwoven systems that shape global product development processes.

In a November talk, PCH Lime Lab co-founder Andre Yousefi provided an up-close look at a global product ecosystem. Lime Lab works with design firms, major companies, and startups to bring products to market, weaving a focus on design for manufacturing and assembly through services from prototyping to packaging engineering. In his talk, Yousefi walked us through how these processes unfold across Lime Lab’s hubs in San Francisco and in Shenzhen, China, noting that in Shenzhen, teams are no more than three hours away from factories and no more than three days away from shipping to 90% of consumers. Several case studies, from Lime Lab’s work with L’Oreal on prototyping smart skincare products to its strategies for optimizing fulfillment systems, illustrated the role of integrated strategies in making or breaking a product’s success. Particularly given the high cost of hardware projects, Yousefi emphasized, products need more than just great design to succeed: they need to be aligned with user needs, markets, and the logistics of a globalized economy.

University of Michigan assistant professor Silvia Lindtner also trained a lens on Shenzhen’s hardware production ecosystem in a talk at the Jacobs Institute this semester. Lindtner’s research focuses in part on the culture and politics of making and entrepreneurship in urban China, and in 2013, she spent a year embedded in a Shenzhen-based hardware accelerator, conducting ethnographic research. In her talk, she shared insights from this research, pointing to the idealism of the maker movement while asking how we might balance this idealism with thoughtful consideration of persistent inequities along race, class, and gender lines. Her talk underlined the complex cultural ecosystems in which global design and production exist — and of which designers and technologists should be conscious.

As the semester came to a close, Steve Vassallo joined us for a talk that, in many ways, brought together the themes raised by Yousefi and Lindtner. Vassallo is a general partner at Foundation Capital; his previous roles have included serving as VP of product and engineering at Ning and leading projects at design firm IDEO. Drawing from this background, his talk laid out a set of principles, along with concrete advice, for designer-led entrepreneurship (read more in his book, The Way to Design, available as a PDF here). Like Yousefi, he encouraged designers to familiarize themselves with the ins and outs of business, complementing their craft with an understanding of how their work will interact with markets. Considering the global scope of these markets, he also emphasized the need to study social, economic, and cultural systems more broadly, arguing for a focus on critically engaged systems thinking in an increasingly interconnected world.

The intersection of design and biology continues to be a rich space for exploration and experimentation — and for meaningful impact.

As part of the Design Field Notes series, Berkeley architecture associate professor M. Paz Gutierrez joined us on this side of campus this fall. In her talk, she shared her genre-bending projects, which often draw from nature for inspiration and materials. Explaining that she sees structures as living laboratories, she took us behind the scenes of projects that exemplify this viewpoint — such as a project in which she has studied bamboo-based craft practices in the Amazon and worked with communities to translate these practices into 3D printing processes, experimenting with materials like palm powders and bamboo/PLA filament mixes that might preserve ecological and cultural benefits while remaining cost-effective.

We explored another intersection of biology and design in a talk from Andreas Bastian, senior research scientist at Autodesk and founder of LimbForge. LimbForge is a nonprofit that develops tools and training for providing patients with 3D-printed prosthetics. In his talk, Bastian delved into the organization’s approach and lessons learned, highlighting how LimbForge has built not just standalone items, but a system of customizable modules and resources that can be applied to match “pretty much any anatomy on earth.” He underlined the role of understanding culture alongside biology, noting that prosthetic care is ultimately not about replacing specific anatomy, but rather about replacing functionality — and that patients’ priorities will vary based on factors like occupation and location. Together, Bastian’s and Gutierrez’s talks presented a compelling view of future interplay between design and biology, as hybrid materials and tools prompt new interactions with structures ranging from sustainable buildings to the human body.

Just as storytelling shapes design, design tools and approaches open new possibilities for storytelling.

In the Jacobs Design Conversations series’ first season, curator Ellen Lupton spoke on design and stories in a precursor to her recent book, Design is Storytelling. In her talk, she discussed how the arcs and techniques of narrative can shape designed interactions. This fall, the flip side of that equation seemed to underlie several talks at Jacobs Hall, as speakers pointed to how design and technology tools are shaping new forms of storytelling.

Early in the semester, Stamen’s Eric Rodenbeck joined us to speak on “telling stories with data.” Stamen is a data visualization design studio that works with clients that have ranged from art museums and scientists to the Dalai Lama, and Rodenbeck’s talk traced the ways that the studio has approached using data to tell stories across these diverse areas. Emphasizing that no visualization can map all information or tell all stories, Rodenbeck explained that Stamen’s team approaches a project as “a visual artifact to ask a specific question about.” From a map of vibrations in a fiber optic cable to a visualization of the influx of global populations to the Bay Area over 150 years, he shared how using design tools to make data visible can prompt new questions, surfacing untold stories in the process.

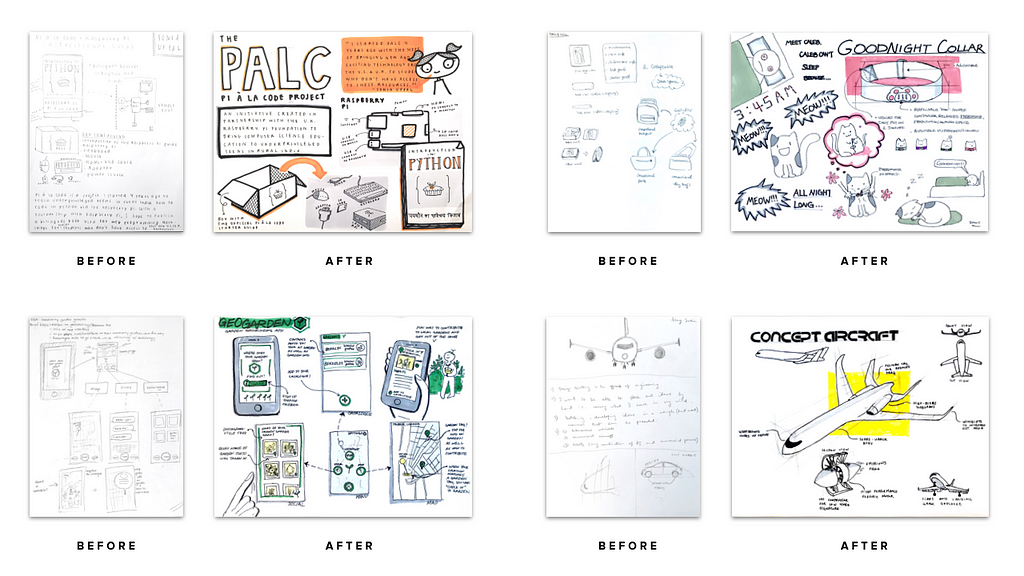

Later in the semester, we heard another perspective on how design and technology tools are shaping storytelling from Pixar artist Tim Evatt, who has worked as a set designer (and occasionally character designer) on films like Toy Story 3, The Good Dinosaur, and the just-released Coco. At Jacobs Hall, Evatt emphasized how much of this work comes down to problem-solving: dimensions and angles need to fit together, the elements that make up a set (from a janitor’s cart in a Toy Story 3 scene to the tiles lining the plazas in Coco) need to meaningfully reflect context, and everything needs to come together to drive the story forward. As he walked us through how these elements come together in collaborative processes at Pixar, moving from hand sketches into complex software environments, he highlighted creative problem-solving at intersections of art and engineering —pointing to a shared skill set that enables effective design in the movies and far beyond.

As we head into the spring semester, the Jacobs Institute community will be continuing to explore these themes, from the students who will travel to Hong Kong and Shenzhen as part of Global Product Development to new designers exploring biology, storytelling, and more in entry-level courses like Bioinspired Design and Visual Communication and Sketching. We’ll also be back in January with a new season of talks: sign up for our newsletter to be the first to hear when we announce the spring lineup.

By Laura Mitchell

Fall talks at Jacobs Hall: Three themes for design innovators was originally published in Jacobs Institute for Design Innovation on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.